The first steps of an art and interdisciplinary research project

by Udo Fon

You never change anything by fighting the existing reality. To change something, you have to develop a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

R. Buckminster Fuller

In the beginning …

… there was a sine wave and two questions: Is there a common perception with which a person from Upper Manhattan can see the world in the same way as a person from Ukraine? And secondly: How many parts of the world do you have to see in order to recognise the whole?

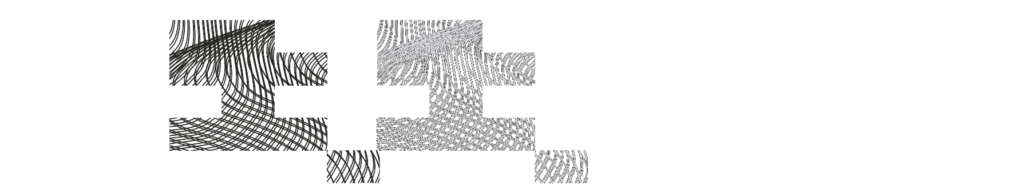

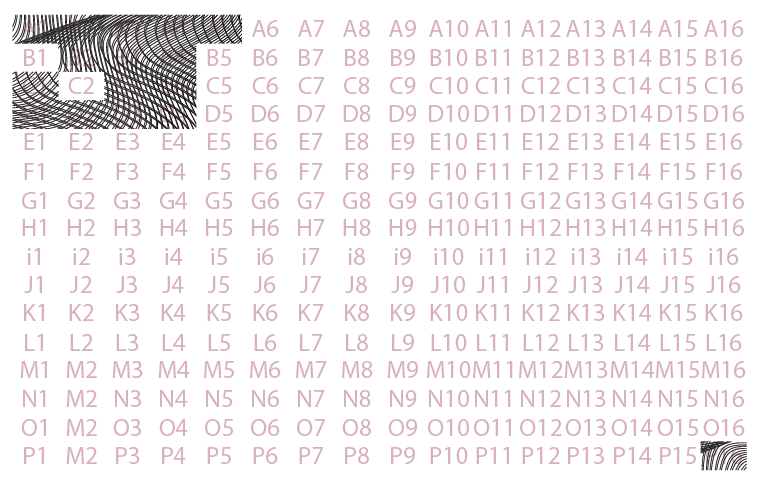

If the ‘whole’ is understood as a living, ever-changing universal resonance, then it can be assumed that only parts of it can ever be perceived. This is explored in the large-format painting The Great Resonance, where the overall size of approximately 20 x 10 metres makes it difficult to see the whole. In addition, the picture is divided into 256 individual images and transferred to different media. Parts exist as real oil paintings in the format of 80 x 130 cm (https://www.saatchiart.com/udofon), parts of the picture only exist virtually as an NFT (https://opensea.io/UFON) and parts of the picture only exist in the imagination of the readers of the model and/or artist’s book created here.

The first parts of The Great Resonance (60D)

were exhibited at the Bildraum 07 gallery in Vienna/Austria in 2015. The pictures A1-A6, B2-B6, C1, C3-C6, D1-D6 were painted in oil on canvas.

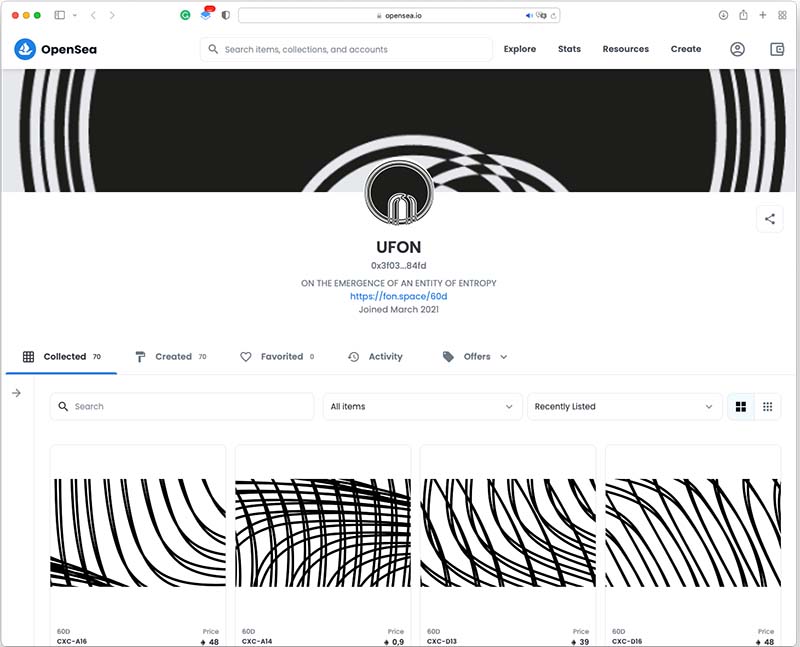

On a virtual level

some elements are available as NFT @ https://opensea.io/UFON

The design of this painting and the development of the underlying theory were largely inspired by resonance phenomena.

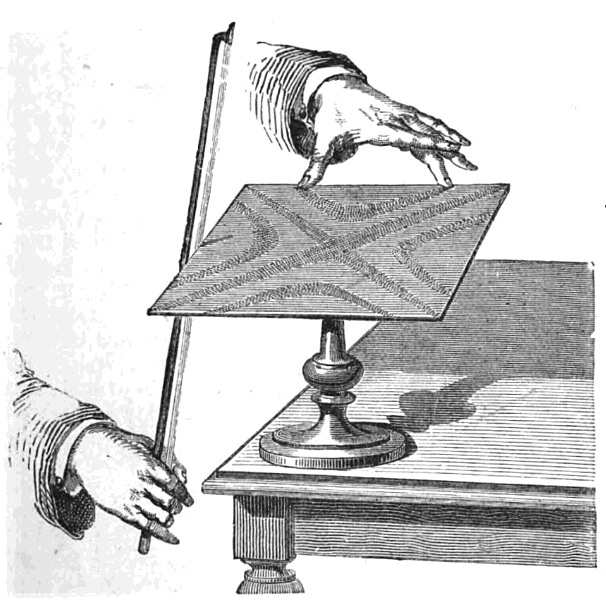

The physicist and amateur violinist Ernst Florenz Friedrich Chladni (1756–1827) discovered unusual geometric patterns in 1787 when he sprinkled sand on a metal plate and stroked the edge with a violin bow. Such patterns were observed as early as 1680 by Robert Hooke (1635–1702) during experiments with glass plates.

In the first half of the 20th century, Hans Jenny coined the term cymatics to describe the accustic effects of sound waves phenomena that produce gemetric patterns. The photographer and researcher Alexander Lauterwasser carried out similar experiments with water in the second half of the 20th century. During his experiments, he discovered shapes of standing waves that in some cases bear a strong similarity to living beings.

The Great Resonance (60D) is also inspired by the theory of Hartmut Rosa: Resonanz. A sociology of world relations.

His theory published in 2016 describes the development of interpersonal resonance conditions that promote or inhibit social interaction.

And is also influenced by the ground-breaking book Act and Image by Warren Colman, which discusses the emergence of archetypal symbols from man’s engagement with his social and material environment.